Deep-sea oxygen discovery calls into question origins of life on Earth

Calls for further investigation into ‘dark oxygen’ phenomenon ahead of deep-sea mining activity.

A discovery in the dark depths of the Pacific Ocean is challenging the scientific consensus of how oxygen is produced and has even called into question how life on Earth began.

Photosynthetic organisms like plants and algae use energy from sunlight to create the planet’s oxygen but new evidence, published in Nature Geoscience, has shown how oxygen is also produced in complete darkness at the seafloor 4,000 metres below the ocean surface, where no light can penetrate.

A team led by Professor Andrew Sweetman of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban, a partner of UHI, made the ‘dark oxygen’ discovery while on ship-based fieldwork in the Pacific Ocean.

Professor Sweetman said: “For aerobic life to begin on the planet, there had to be oxygen and our understanding has been that Earth’s oxygen supply began with photosynthetic organisms. But we now know that there is oxygen produced in the deep sea, where there is no light. I think we therefore need to revisit questions like: where could aerobic life have begun?”

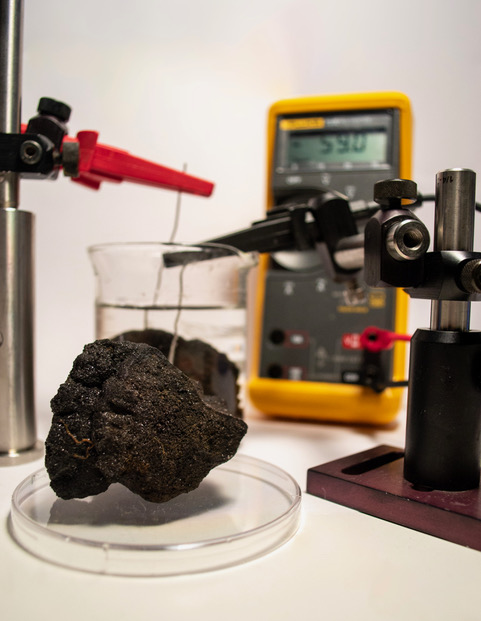

The discovery was made while sampling the seabed of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone to assess the possible impacts of deep-sea mining. This process would extract polymetallic nodules that contain metals such as manganese, nickel and cobalt, which are required to produce lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and mobile phones.

In the experiments, Professor Sweetman and colleagues found nodules to be carrying a very high electric charge, which could lead to the splitting of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen in a process called seawater electrolysis. Only a voltage of 1.5 V is needed for seawater electrolysis to occur – the same voltage as a typical AA battery. The team analysed multiple nodules and recorded readings of up to 0.95 volts on the surfaces of some, meaning that significant voltages can occur when the nodules are clustered together.

Professor Sweetman now says that more investigation into ‘dark oxygen’ production is required during deep-sea mineral extraction baseline investigations as well as an assessment of how sediment smothering during mining may alter the process.

He said: “Through this discovery, we have generated many unanswered questions, and I think we have a lot to think about in terms of how we mine these nodules, which are effectively batteries in a rock.”

“When we first got this data, we thought the sensors were faulty, because every study ever done in the deep sea has only seen oxygen being consumed rather than produced. We would come home and recalibrate the sensors but over the course of 10 years, these strange oxygen readings kept showing up.”

“We decided to take a back-up method that worked differently to the optode sensors we were using and when both methods came back with the same result, we knew we were onto something ground-breaking and unthought-of.”

Professor Sweetman has previously been involved in identifying marine protected areas around the Clarion Clipperton Zone, assessing the biodiversity in certain areas where potential deep-sea mining should be avoided.

However, he says this assessment may need to be reviewed as this new evidence of oxygen production was not factored into the findings.

Species such as rat tail fishes can be found in the deep sea

SAMS Director Professor Nicholas Owens said: “In my opinion, this is one of the most exciting findings in ocean science in recent times. “

“The discovery of oxygen production by a non-photosynthetic process requires us to rethink how the evolution of complex life on the planet might have originated. The conventional view is that oxygen was first produced around three billion years ago by ancient microbes called cyanobacteria and there was a gradual development of complex life thereafter. The potential that there was an alternative source requires us to have a radical rethink.”