The Iolaire Impact

Soon the Inner Isles were fading behind, rugged rock Rona and misty Isle of Skye were vanishing on the port quarter. Now with a pitch and roll we were in the open sea … I had a horrid dream. I saw my father talking to me. I could feel his breath, his torpedo beard touching my cheek. “Don, be careful,” he said … I work up with terrible foreboding. … then came a louder scraping vibrating noise and a terrible impact - simultaneously the boat lurched at an awful angle catapulting us mercilessly against the lee side of the chart-house … The scene was terrible to behold. We were used to mines, torpedoes and shell fire but this struck fear in our hearts. We knew we were trapped, as no life-boat could live in that maelstrom. The most powerful swimmer would be a toy. [1]

These are the words of Donald MacDonald from Lochs on the Isle of Lewis recounting his harrowing experience on HMY Iolaire as he and over 200 others made the crossing to Stornoway on New years Eve 1918. Early in the morning of 1st January the boat struck the Beasts of Holm just outside Stornoway harbour. The Iolaire rapidly broke up and sunk. There were only 82 survivors. Virtually all on board were from Lewis, Harris or Berneray and there was scarcely a family on Lewis untouched by the disaster. It created a collective trauma perhaps exceeding that of Grenfell, the Twin Towers or Aberfan. It has echoed down the generations and fed into every social, cultural and spiritual process that has shaped island life across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The project and talk ‘The Iolaire Impact’ does not seek new material on the disaster as there is little new to discover. Instead, we look to the legacy of coping with the disaster. We have sought out stories of how families and communities dealt with the impact across the generations.

What has emerged is a story of silence and internalising of grief based on the self-effacing, stoical and spiritual nature of an island culture with a sad tradition of facing collective trauma. But coping evolved. Over time it became less individualised and more collective. A change mainly driven by the passing of the generation most closely affected, by publications, radio and television programmes on the disaster and by the unveiling of the first official monument to the disaster in 1960. Over time, then, the disaster has become a difficult, emotionally challenging heritage.

To learn more, join us on Thursday 13 October, 17.30-18.30 for the History Talks Live event, 'The Iolaire Impact' with Professor Marjory Harper and Dr Iain Robertson, from the UHI Centre for History. This is an online-only event, delivered in partnership with the Highland Archaeological Festival. For more information and joining instructions for this free event, please visit our History Talks Live website.

[1] Stornoway Gazette, 10 August 1956

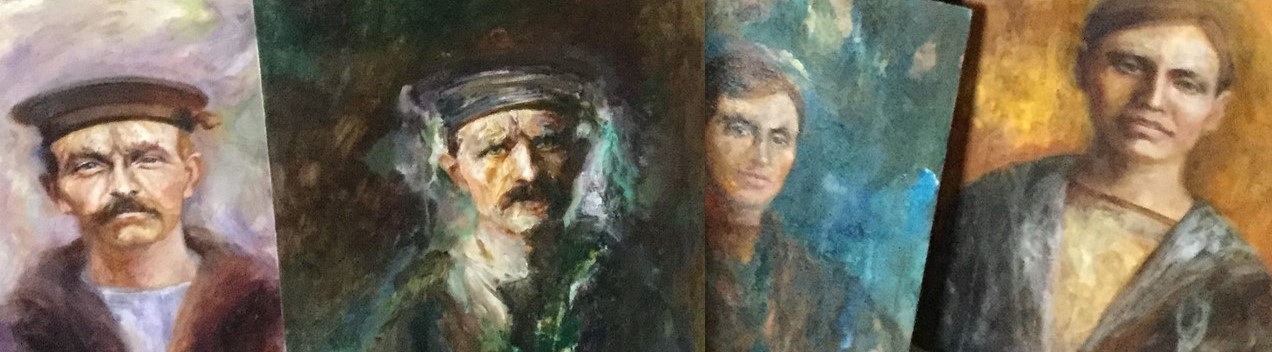

Image: Collage of Margaret Ferguson's Iolaire 100, c.2019

Please note this content is only accessible through the link shared on our social media channels.